By Alex van Daalen, G12

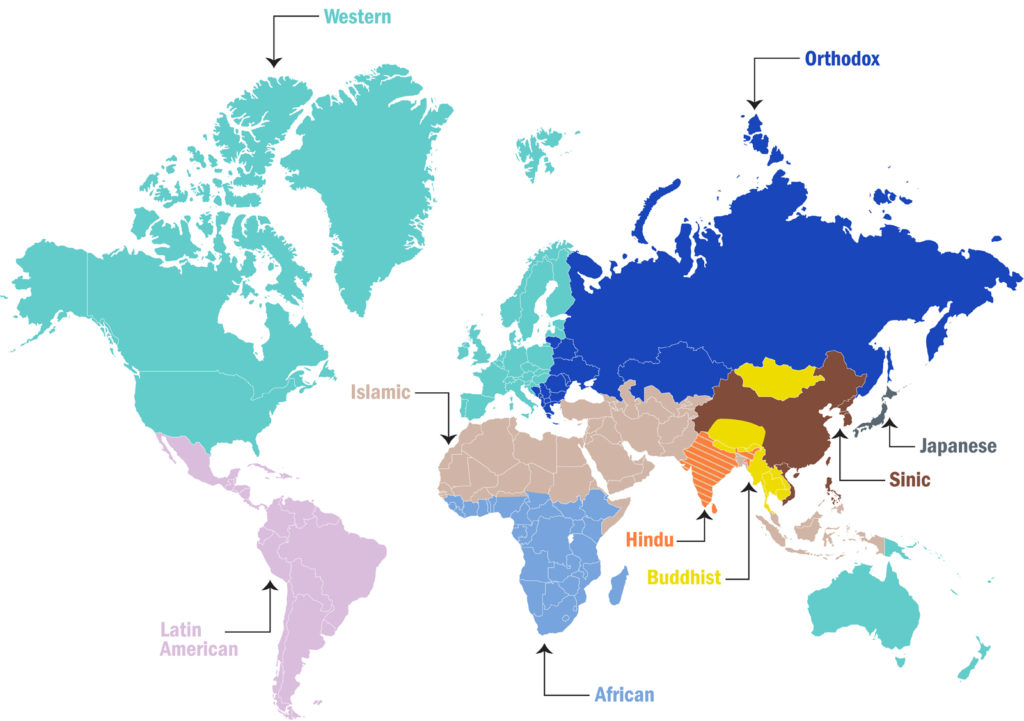

Time and time again we hear devastating news from around the world, whether it be war, terrorism or discrimination. Though it may feel as though we live in rough times, countries are more dependent on each other than they ever have been due to the power of trade and the interconnectedness of global capital. The political and economic spheres have over the subsequent decades become increasingly dependent on one another, giving rise to ideologies that are derived from this relationship. The surge of capitalism and globalisation has produced an immense amount of wealth that on average makes people far better off than ever before, wherein people usually don’t feel the need to resort to violence to gain access to resources. Nevertheless, conflict still exists and tensions between nation states are still prominent. To a large extent, this can be attributed to the cultural divides within the globalised world. Culture and cultural identities, which at the broadest level are civilisational identities, are shaping the patterns of cohesion, disintegration, and conflict in the post-Cold War world.

Modernisation is the process by which countries industrialise. This refers to achieving technological innovations, spreading literacy and becoming globally competitive. Often, this process has been equated to Westernisation, which supposes that as cultures modernise they tend to Westernise. Yet, it can be argued that the world has in fact become less Western in its process of modernisation. This is on the basis that modernisation gives cultures a great deal of power, giving rise to unique systems of values and beliefs that constitute a given civilisation.

Language and religion are deemed two of the most important factors that shape a culture. The notion of a shared language helps people connect with and relate to one another. Similarly, a shared religion provides groups of people with a set of values that unite them. The resurgence of indigenous languages in former European colonies, as opposed to retaining the language of their occupier, demonstrates the resistance to Westernisation by cultures with deep roots. There has also been a trend for religions to return to a more fundamentalist direction as a result of the ideological void left behind after the collapse of the communist system post-Cold War.

The interactions between hard power and soft power indicate the success and failures of civilisations. Namely, the relationships between military power, economic power and cultural capital. Cultural capital enables countries to sway other countries in favour of a certain position, with things such as films, music and other cultural products. These transmit certain values and perspectives that a culture has on other cultures. The Korean wave is an example of the transmission of Korean culture across East Asia and the rest of the world, generating confidence in the cultural commonalities from this geographical region. This follows Asia’s newfound economic power that has resulted in a gradual shift of the balance of power from the West to the East, and makes the East more culturally relevant. It provides them leverage by which they can defy Westernisation and develop their own unique cultures while still advancing modernisation.

The resurgence of religion, particularly Islam, connects with the development of non-Western cultures. The changing demographics in different regions of the world such as the Middle East, China and Africa resulted in a newfound strength that allowed these civilisations to modernise in their own rights. At the same time, with the sense of isolation that modernisation brings as people move into cities and take on corporate jobs came the need for identity and stability, which was found in religion. Consequently, these people were more likely to elect religious leaders which then became more and more radical in order to gain support in their respective countries.

An important determinant of civilisation is its core state, which has the greatest cultural and political strength among the nations in the civilisation. Today, key core states include China in East Asia and the United States in the West. These core states are concerned with the preservation of culture by controlling and supporting other countries in the civilisation. Conflicts would then tend to only occur when these core states clash with ones from other civilisations. The absence of a core state in Islamic civilisation reveals the importance of having one, in the sense that internal and external conflicts are more prone to occur.

There is an apparent struggle between universalism and uniqueness, in which Western civilisation appears to strive for universalism. Meaning that its values of individualism and self-determination are pitted against values of community and authoritarianism found in other civilisations; this supposes that these values are superior to ones from other cultures. However, the pursuit of Western universalism is met with friction from other culturally unique civilisations. This suggests that Western civilisation should instead focus on its uniqueness, and protect itself from the encroachment of external rising cultures.

The ideal of multiculturalism refers to the existence of multiple cultures within one country, whereas multicivilisationalism refers to multiple competing civilisations in the world. The danger that multiculturalism presents is that it shifts a country’s identity to merge with another civilisational identity. In doing so, said civilisation would ultimately lack a cultural core for people to identify with. On the other hand, multicivilisationalism presents an ideal that suggests that distinct cultures exist in different parts of the world as distinct civilisations.

All in all, we can attribute certain cultural clashes to the notion of protecting civilisational identity. This links to the personal identity that one has with regards to their national identity. The conflicts between different cultural groups may ultimately never be resolved, but taking into consideration that this is the case it may be a fruitful endeavour to accept the cultural divides and work alongside them in pursuit of common humane interests. Thus, we should not aim to make a uniform global culture, but instead learn to accept the distinctions that define different societies.

Cover Image courtesy of Sid Meiers, Civilization VI